Published on: October 25th, 2006

Does God have a name?

Simple enough question, but the answer may not be

quite so simple. When God told Moses to go to Pharaoh to demand that

the Hebrews be set free, Moses asked God, “Suppose I go to the

Israelites and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to

you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ Then what shall I tell them?”

(Exodus 3:13) Was Moses being presumptuous? And what does God’s answer

mean?

God heard Moses’ question, and responded, “I AM

WHO I AM.” God adds, “This is what you are to say to the Israelites: ‘I AM has sent me to you’” (Exodus 3:14).

We asked Dr. Walter Kaiser, Jr., recently retired president of

Gordon-Conwell seminary, what he thinks about Moses’ question and God’s

response. “God did reveal his name; that was the point of responding

with

Yahweh,” says Dr. Kaiser. “It means ‘I will be [there].’

His name is formed by the verb ‘to be.’ Besides this, he is addressed

elsewhere in scripture by many of his qualities and attributes.”

In other words, God answered Moses — with a verb. What is translated “I AM,”

YHWH, stems from the Hebrew root

hayah,

“to be.” Bibles variously translate this as “I am who I am,” or “I will

be what I will be,” or something similar. Most evangelical believers

have adopted Yahweh as the way to spell out the pronunciation of the

four letters (though not all scholars agree with this).

However pronounced, the

meaning God intended for Moses

isn’t something you can easily wrap your mind around. Gary Deddo,

theologian and associate editor with InterVarsity Press, says that

Moses’ question and God’s answer are important to grasp, even though

it’s hard. We asked Gary if he thought Moses was presumptuous to ask God

to give a name as a sort of calling card for the Egyptians. “Well, it

would be presumptuous for us to think

we can name God any more

than we can create an image of God,” says Gary. “And God’s reply to

Moses does address any temptation to presumptions. But more

particularly, Moses’ encounter indicates that God cannot be compared to

any created thing. God is the incomparable one. The God of the Jews can

only be named and defined in terms of himself.

I am, that I am.

In using this name, God indicates that he does not depend upon anything

else — ‘I am the being one, the living one, the one alone who was, is

and will be.’”

What’s in a name?

Names are how we identify people. We also use nicknames, attributes and roles. In

Through the Looking Glass,

the White Knight offers Alice some insight about names and labels that

may shed some light on this. He proposes to comfort a tired and

discouraged Alice by singing her a song:

“Is it very long?” Alice asked, for she had heard a good deal of poetry that day.

“It’s long,” said the Knight, “but it’s very, very beautiful.

Everybody that hears me sing it — either it brings the tears into their

eyes, or else —”

“Or else what?” said Alice, for the Knight had made a sudden pause.

“Or else it doesn’t, you know. The name of the song is called ‘Haddock’s Eyes.’”

“Oh, that’s the name of the song, is it?” Alice said, trying to feel interested.

“No, you don’t understand,” the Knight said, looking a little

vexed. “That’s what the name is called. The name really is ‘The Aged

Aged Man.’”

“Then I ought to have said ‘That’s what the song is called?’” Alice corrected herself.

“No, you oughtn’t: that’s quite another thing! The song is called ‘Ways and Means’: but that’s only what it’s called, you know!”

“Well, what is the song, then?” said Alice, who was by this time completely bewildered.

“I was coming to that,” the Knight said. “The song really is ‘A-sitting on a Gate’: and the tune’s my own invention.”

Clear? Right. Well, maybe that didn’t shed a whole lot of light (but

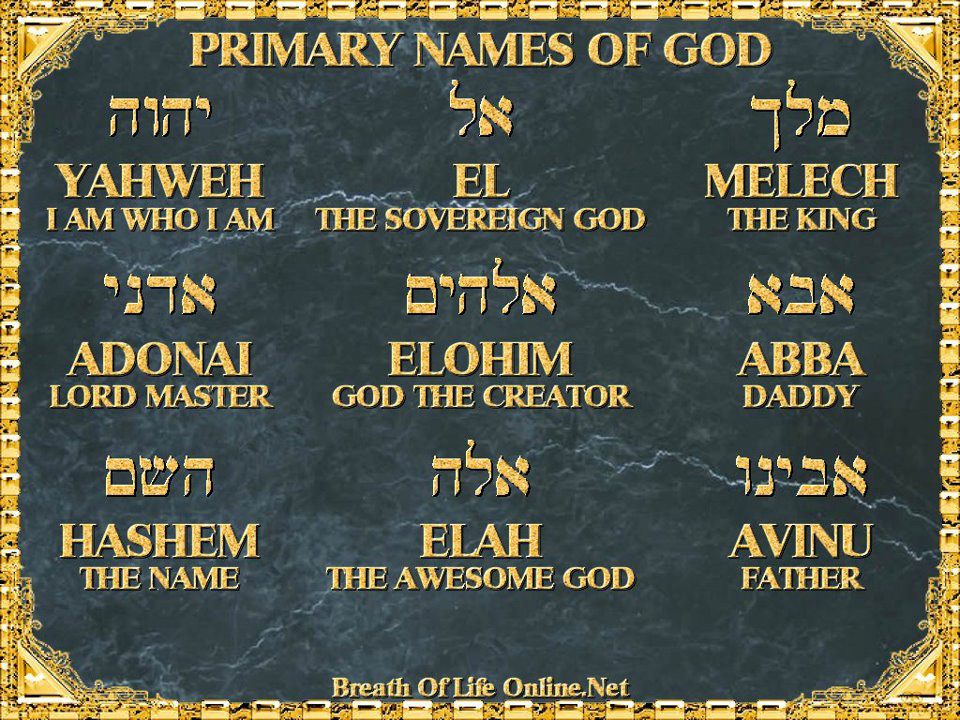

it’s great fun to read!). All this is simply to say that while we call

God a number of “names” (Elohim, El-Shaddai, Adonai, Theos, Father,

Abba), it’s hard (but very important) to nail down what God’s own,

self-declared name really means for us, because it isn’t just something

God is called. “I AM” carries the essence of the

God who is.

Confusing, perhaps, but Gary points out that God didn’t just leave us

with his words to Moses. “It isn’t that God cannot be known at all,” he

notes. “Even this negative message — that God can only be named in

relation to himself — is a revelation. We cannot assume that since we

cannot name God in terms of some created thing, that God himself cannot

reveal or name himself to us. And that is the claim of Jesus and his

witnesses. God said no to our creating images and idols in order to

reserve a place for him to ‘image’ himself to us and in fact to finally

name himself.”

I’ll just show you who I AM

The history of God’s self-revelation reaches its fulfillment in the

coming of Jesus Christ. Jesus puts a name and a face on God for us. And

he does so as God himself. “Jesus is the self-revelation and self-naming

of God,” says Gary. “We don’t name or give an image to God. Notice that

even in the birth story, Mary and Joseph are told by an angel what to

call him — Jesus, ‘God saves.’”

Finally, Gary points out, Jesus himself tells us how to address and

call upon the name of God. We are to baptize in the name of God the

Father, Son and Holy Spirit. “That is the one name we are given and

authorized to pass on. Notice that in this name, each identity in the

Trinity refers not to Creation or a relationship with Creation, but

rather refers to the others

before and

independent of

anything in creation. The Father is the Father of the Son. The Son is

Son of the Father. And the Spirit is the Spirit of the Father and the

Son. God is naming himself in terms of himself and his own inner

personal and Trinitarian life.

So does God have a name? Yes, in the Old Testament, the high point

was the personal title of the God of Israel and Creation: Yahweh. In the

New Testament, God shows up in the person of Jesus bearing the very

stamp of the image of God (

Hebrews 1:1-4).

“He takes us to the Father and sends us his Spirit,” says Gary. “This

is the God who is. God has named himself and revealed himself to us in

Jesus Christ.”